THE INTERVIEW

January 8th, 2022

CHRIS M. ALLPORT

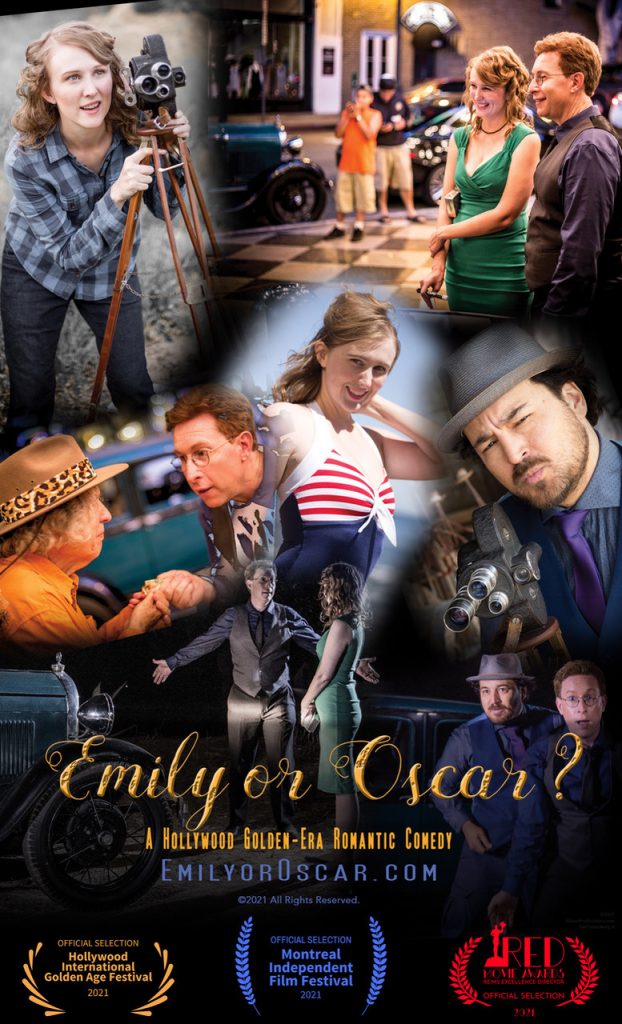

DIRECTOR OF EMILY OR OSCAR ?

HONORABLE MENTION

BEST FEATURE – 2021 NOVEMBER EDITION

Many people are fascinated with the performances they see on streaming or the screen and attribute that performance solely to the actor. It became clear to me, early on in my child acting days, that cinema, tv and music were actually comprised of much more than just a headliner who is credited. Excellent performance, rather, is a two-way dialogue between actor and director. A great director works in sync with their actors, and conversely a great performer relies on their director for guidance.

It was during my teen years as an actor, that I recall a handful of times when I was asked to step behind the camera to fill-in as a director. The first time, I was actually singing in a Christmas choir on a live television broadcast to Berlin from the Paramount Studio lot in Hollywood. Ten minutes before live-to-air, a conflict between the music director and producer came to a head. I was unaware of what the quarrel was regarding. The artistic personality clash ended up with the music director throwing the baton down and storming off, with now only eight minutes to live broadcast. Without missing a beat, the producer picked up the baton and singled me out of the choir. He had the pianist show me how to keep time, and I was pushed out on stage as the music director, less than a minute before the live broadcast. At the time, I didn’t think much of it, I just did what was being asked, and the broadcast was a success! The folks watching the live broadcast on the other side of the world had no clue about the conflict, or any potential issues. They just saw a lovely Christmas television broadcast — and I was music directing.

It was years later that I realized the producer had trusted me for my leadership. Leadership is really the strongest quality a director can have. Everyone on set is going to be amazingly talented. But there is usually only one person who’s job it is to make sure that all of the individual artistic visions that are present on set fit together seamlessly. The seamless transitions are really what ultimately keep the audience engaged.

During my years at Loyola Marymount University in the School of Film and Television, I was asked to direct William H. Macy in narration for a documentary about the Choctaw Code Talkers, who helped crack the Nazi codes during the Second World War — ultimately paving the path for the Allied victory in Europe. As you can imagine, I was a little nervous when Mr. Macy entered the studio. Not to meet him, for we had worked together before on Mr. Holland’s Opus, but nervous to direct such an accomplished actor. I was communicative and frank with him about my reservations, and that I was still in film school.

“Every great actor has a great director,” Mr. Macy replied to me, “and today, you are my director.”

The confidence he instilled in me, caused me to rise the occasion. I was being asked to listen critically to the narration, and give feedback, making sure his narration matched the picture. Rather than declining from the post in submission, I rose to the challenge. Mr. Macy and I were having artistic conversations about how the material worked together. It was then, that I began to garner a reputation for keeping a cool head around high-profile actors, and also when I started to see a path forward as a director-for-hire. Subsequently, I was asked to directed then-president of the United States, Bill Clinton, and other politicians for their on-camera television presentations.

While, I can not profess to fulfill their shoes — and each filmmaker must ultimately speak with their own voice — my cinematic aesthetics have been deeply influenced by the following list of writers, directors and creators (in no particular order): Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Nora Ephron, David Lynch, Woody Allen, the Cohen Brothers, Wes Anderson, and Steven Spielberg.

Each one of these giants has had their own consistent aesthetic, which you can see develop and bloom over the trajectory of their careers. The cool thing to me, is that the artwork they have created is intrinsic. Once you experience it, you can’t un-see it. Chances are if you’ve seen a movie by one of these — just once —that you will not be able to forget it. The images and stories will indelibly be written onto the childlike imagination that resides deep within all of us.

“Every great actor has a great director,” Mr. Macy replied to me, “and today, you are my director.”

Thank you for acknowledging these wonderful actors. Within my soul there is a deep affinity that I have for actors. While many times, people outside of our industry conceive of actors being self-centered and detached from reality, I have often found quite the contrary — but you have to look deep beneath the surface. I often find that the most interesting people to watch are not actually trained actors, but have some sort of unique quality that compels fascination from others. In Emily or Oscar I have selected a compliment of both trained actors and people that I have encountered in real life.

Please keep in mind that I am speaking here from my own experience as an actor, a person who is constantly around actors, and as a director. My experience does not necessarily mean universal truth.

Take an actor away from set, and you might find that you have to dig deep and offer something they desire in order to engage in a meaningful conversation. Yet, still waters run deep. Most seasoned actors are so incredibly full of life experience, are deeply in touch with their emotional life, and are highly empathic when it comes to sensing and feeling out where another person might be. Actors are not always right either, but something that makes them so interesting to me is how deeply they hold their convictions. That tenacity is what wins your heart and empathy when you see them. In good writing, you will find that there is almost always some redeeming quality to the antagonist, that even a normal person can identify with.

Being an actor is most certainly an uncertain style of life. But at the end of the day, each actor is still a human being. That is the most important part. I think it is important to try to understand where each actor is coming from, and what they want, to see if its possible that you can integrate their goal into your own directorial goal, so that you are both focused on the same objective. It is not always possible, but when the director and actor are focused on the same objective, that is when the work becomes really fun!

Actors are not always right either, but something that makes them so interesting to me is how deeply they hold their convictions.

In Emily or Oscar, as a directing approach, I chose to bring the story and the production as close to who the actors are in real life as possible. Take for instance my character of “The Prophet,” played by world-renowned poet, Stevie Kalinich. Stevie has such a unique view of the world and his own way of interacting with it. I crafted the role of The Prophet to meet Stevie’s viewpoint. In that way, I did not necessarily need a trained cinema actor for that role. The point of that character is to get protagonist “Sam Feldman,” played by myself, to see the world in a different way.

Casara Clark on the other hand, who plays the title role of “Emily,” is a brilliant, trained actress. While we worked together to craft the role of “Emily” close to her vision, she also brought her chops to the final script in a really tasteful way and is truly fascinating to watch on-screen.

Susan Blakely, in the role of “Bev Hardin,” Sam Feldman’s agent, was so graceful to lend her Golden Globe-winning talents as a co-star in this project. Susan Boyd Joyce too, co-starring in the role of “Mary Pickford,” was incredible. Both were super-pro and easy to work with.

Los Angeles Opera singer, Aleta Braxton, who is also one of the film’s Executive Producers stepped up to the plate when we needed to fulfill the role of the Emcee, introducing Emily’s song I Just Wanna Be Found. A natural on-stage, Aleta’s character invites Emily to the stage, ensuring the audience understands the importance of the performance that is coming ahead. Aleta is also a seasoned voice over actor, and brilliantly vocally performed the off-camera Screenland Magazine headlines, which tie historical plot points of the film together.

Something to be said about almost everyone in the cast, is that we have all worked with each other in different capacities for years. Most actors are not “just an actor.” Like dodecahedrons, actors usually have at least twelve things happening at one time, in all sorts of different realms. I think that is what makes them so fascinating.

From an early age, I began training in a variety of specific disciplines within the performing arts. Fortunately, many of my teachers were old Hollywood icons. Discovered by former Broadway dancer and Radio City Rockette, Madilyn Clark at the age of seven, I was thrust into acting, singing and dance classes. I remember many people asking me if I’d rather have a normal childhood. I didn’t understand what they were talking about — because performance life was completely normal and natural to me. I felt most comfortable on a stage or in front of a camera.

The education that was instilled in me by Hollywood legends like Debbie Reynolds, Donald O’Connor, Alan Young and Stan Freberg, along with a host of other performer / teachers, who instilled a consistent work ethic and drive for excellence. The coaching was not just academic and far from surface level. My training in acting, singing, dance, directing, editing, screenwriting and musical composition runs deep. Academically, I excelled and graduated with honors from Loyola Marymount University. However, theoretical knowledge has never been enough for me. It is at the crossroads of theoretical and practical learning where my artistic viewpoint exists. As a writer and director, I think it really helps to look at a project through each of the different disciplines to get the best overall viewpoint.

I remember many people asking me if I’d rather have a normal childhood. I didn’t understand what they were talking about — because performance life was completely normal and natural to me.

I often get asked if it is difficult to act and direct at the same time. Initially it can be. But necessity is the mother of invention, and I developed techniques to delineate which lens to look through at what time. For instance, if I was not in the scene, I completely divorced myself from the character of ‘Sam Feldman,’ and only looked at the scene through the monitor, as a director. There were a certain set of consistent traits that I had developed for ‘Sam’ to immediately be able to re-embody the character. I also relied on second-unit directors to be my second set of eyes. I would ask for specific feedback about my performance from them, and then integrate the notes into my overall vision for the film. Some of these amazing collaborators, including R.J. Lynn, Ismaël Lotz and Robert J. MacColl, should be mentioned at this point for they watched out to make sure that the character of “Sam Feldman” was being properly portrayed. I would often do two or three takes and then review the footage in the monitor to make sure I was getting what we needed for “Sam.”

Ismaël Lotz also plays “The Mysterious Gentleman,” the character is an homage to Douglas Fairbanks. A director in his own right, Ismaël is a gifted filmmaker from The Netherlands who can be found both in front of and behind the camera.

Between 1910 and 1920, there was such a passion and drive for artistic independence — which is the force that birthed Hollywood Cinema. Its originators were initially escaping studio control and film camera patents from New York executives. When Pickford, Fairbanks, Chaplin and Griffith came out west, they not only discovered more freedom on the western frontier, but plentiful light, and boundless diverse, picturesque landscapes.

Today, corporate control runs Hollywood — and it does have incredible value. I have spent the majority of my career serving as a journeyman actor and director for hire in the Hollywood studio system. There are some stories however, that are best told independently, and that is the space where Emily or Oscar was conceived. It was birthed with the ideals that Pickford, Fairbanks, Chaplin and Griffith had in mind — putting the artistry first, without executive control in the creative process.

Box office receipts have always been a driving force behind which movies get made and which ones don’t. But I do think there are some amazing stories out there, compelling to audiences, that never see the light of day. In a certain sense, the commercialization has always been a part of movies from the beginning. Cinema is the most immersive and comprehensive art form in the world, and I think its power was discovered pretty early. So really, what has changed is not just acess to smaller, more powerful and affordable cameras, microphones and tech, but more importantly also style. You can see how subtle performance styles are today compared to a hundred years ago. But, it was really Mary Pickford who first introduced that simple filmic acting style of almost doing nothing on camera — and that is the style that seemed to fascinate audiences.

The biggest difference today is the access to cameras and technology at an affordable price. There is still significant expense, but you can move into production in the low tens of thousands of dollars, as opposed to low millions. I think that lowers the bar a little for indie projects to start. That being said, I don’t like the idea of abandoning classical rules of storytelling, or the arts of screenwriting and actual cinematography. Just because a modern camera “has autofocus” doesn’t mean that you should use it. There is something magical that speaks to audiences when sticking to original film exposure techniques, and translating those parameters numerically into the digital realm.

The story of Emily or Oscar was initially compelled by some restoration work that I was doing on the old Mary Pickford films. My long-time friend and brilliant composer and violinist, Maria Newman, was creating these intensely beautiful neo-classical scores that fit the restored silent films like an exquisitely tailored gown. I became fascinated with the subtlety of Mary Pickford’s acting, in relation to the more melodramatic stylings, left over from Vaudeville, that were still popular a century back.

Maria, coming from such pedigree of film scoring royalty, voiced these “silent” flickers with a sweet violin, plucky strings, rompy piano and quirky percussion. The resulting scores are so intricately synced with the picture, even when played live, that they work like a Swiss watch — not only keeping time, but enhancing the storyline so clearly, that it there is almost a mandatory compulsion for everyone to watch and listen.

As I put Emily or Oscar together in post, I realized that the score would not work as a softly generic, or padded background, or styled too modernly. As such I realized that various voices would need to blend the old world with the new. As a result, certain phrases would be needed to step out almost as character solos throughout the film. So I called upon the talents of several incredibly gifted colleagues to work with me, lending their talents to get the musical tone of each scene just right. Maria Newman lent her Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm score. Dan Barbenel, who also plays ‘The Wandering Minstrel / Charlie Chalpin’ lent his perfectly adapted song Sunset and Vine (a Fools Paradise), as well as an number of piano and guitar cues that were so brilliantly improvised to picture in certain scenes. David Fick and I composed the more traditional orchestral score cues with strings, harp, piano, woodwinds, and orchestral percussion, and I wrote the three main songs in the film, I Just Wanna be Found, I’ve Lived a Thousand Lifetimes, and Crashin’ to the Other Side. The Los Angeles Recording Choir and Orchestra performed these cues under my own music direction.

The entire point of a good score, is to do more than just hang on to an audience’s attention. One can do that with library cues, but more importantly, the score needs to convey additional emotive and story elements to the scene. The music also can’t get in the way of the actors, so really, each note of each phrase needs to be tailored to the picture.

The resulting scores are so intricately synced with the picture, even when played live, that they work like a Swiss watch — not only keeping time, but enhancing the storyline so clearly, that it there is almost a mandatory compulsion for everyone to watch and listen.

I would say it its much less complicated to produce a film today than in the golden era. That isn’t to say that it’s easy. Once again, technology has opened doors for us, but the craft still needs to be upheld first and foremost.

Technology has opened doors for us, but the craft still needs to be upheld first and foremost.

Senja Chronicles is a very cool action/adventure streaming series that I am writing in partnership with Swedish director Fansu Njie. Our series is based in Scandinavian folklore, and historical fiction, as modern special ops-soldiers encounter vestiges of WWII-era Nazi encampments and relics from the Vikings.

Additionally, I’m currently in production on The Sound of Gold, a music documentary about the legendary Gold Star recording studio in Hollywood that recorded major indie hit records from 1954 – 1984. Some of the majors that came out of Gold Star include, Eddie Cochran, Richie Valens, Brian Wilson & The Beach Boys, Buffalo Springfield, Phil Spector, The Wrecking Crew, Sonny and Cher, and Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass.

My services as a writer and director are currently available in the North American and European markets.